|  | (source: ITEdge News) |

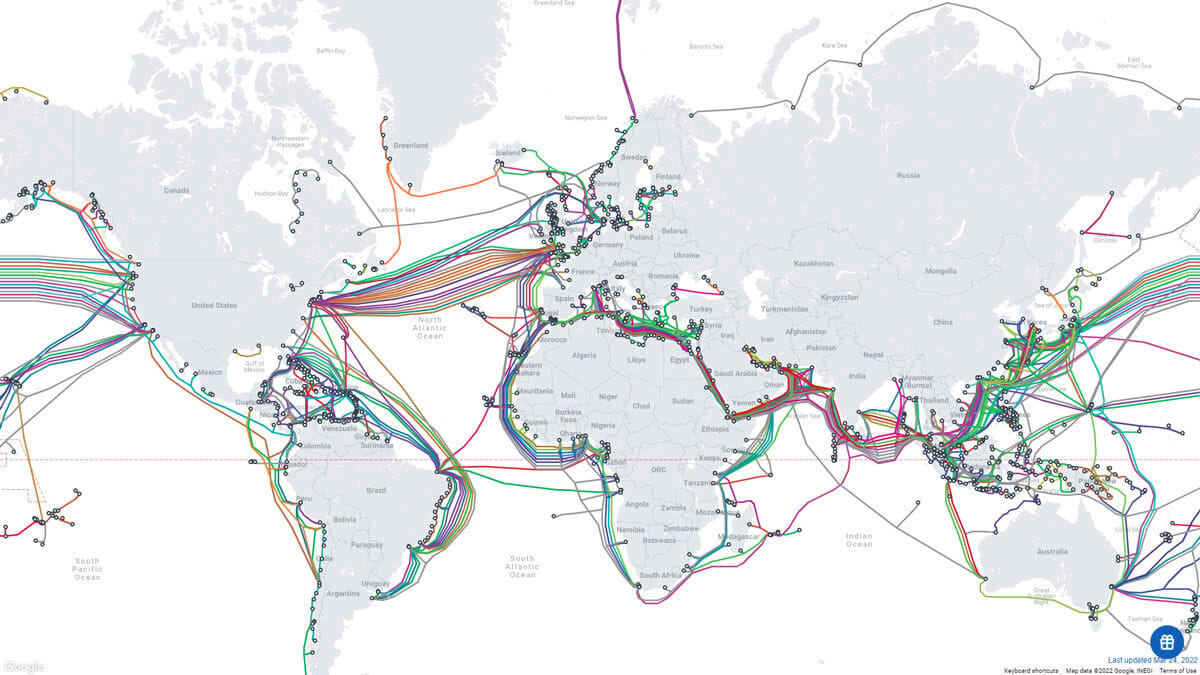

| The modern world runs on the internet. But few people know how it moves around the globe. There is a large network of undersea cables that carry most of all global data. They link continents, allow instant communication, and make global trade possible. Because they are so important, they have become a focus of geopolitical power. States, companies, and even armies are competing for control and protection of these cables. | What are undersea cables? | Undersea cables are thin fiber-optic lines that lie on the seabed. They send information as pulses of light across thousands of miles. More than 95% of global internet traffic moves through them. Satellites play only a small role. Cables are much faster and can carry more data. A single cable can transmit terabits of information every second. This means that almost everything people do online depends on them. This includes video calls, financial trades, cloud storage, or social media. |  | (source: Energy Industry Review) |

| A mean of power | Whoever builds, owns, or protects them gains strategic influence. For most of history, Western powers dominated this space. In the XIXth century, Britain controlled telegraph cables that tied together its empire. Later, the U.S. became the main power in the global cable network. U.S. companies like AT&T and tech giants such as Google, Meta, and Microsoft now own or co-own many of the world's key routes. This gives the U.S. not only commercial advantage. But also, geopolitical leverage. It can shape standards, secure data flows, and even monitor communications when national interests are at stake. | But this dominance is now being challenged. China has become a key player in the undersea cable industry. Companies like Huawei Marine (now HMN Tech) have built or serviced hundreds of cable systems. China sees this as part of its Belt and Road Initiative—a plan to expand its global reach through infrastructure. Control over data routes can strengthen China's role in world trade and diplomacy. But it also creates tensions. The West worries that China's technology could allow data spying or give Beijing a strategic edge. As a result, the U.S. and its allies have blocked Chinese firms from building certain cables or linking directly to sensitive regions. One example is the Pacific Light Cable Network. It was meant to connect Los Angeles and Hong Kong. U.S. authorities stopped the Hong Kong leg because of security concerns. | | | | | Security challenges | These disputes show how undersea cables have become a front line in digital geopolitics. Like oil pipelines in the past, they are both a source of cooperation and conflict. States must work together to lay and repair cables. But they also compete to control the routes. The geography of the seabed adds another layer to this struggle. Many key cables pass through narrow chokepoints. These include the Suez Canal, the Strait of Malacca, or the English Channel. These spots are vulnerable to damage, sabotage, or surveillance. During wars or crises, cutting a few cables could isolate a state. Few years ago, cables near Norway and the Shetland Islands were damaged. This raised fears of sabotage linked to great-power rivalry. | Because of these risks, many states now treat cable security as part of national defense. The U.S., U.K., and France have naval units that monitor undersea infrastructure. NATO has created a special center to protect underwater assets. This includes cables and pipelines. Japan and Australia are also investing in regional networks to reduce their reliance on single routes. Having multiple cables connecting the same places can make the network stronger. But the cost is high. Not all states can afford it. Many developing states rely on a few critical cables. This makes them more vulnerable to both damage and political pressure. | Legal issues also matter. Undersea cables cross international waters, meaning no single country owns them. They are protected under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which allows freedom to lay cables. But enforcement is weak. If a cable is damaged, finding and punishing the culprit is hard. | The private sector as a key player | Private companies play a big role too. Tech giants are not just users of cables. They are now the main builders. Google owns the Dunant cable between the U.S. and France. Meta has invested in 2Africa, one of the largest cable projects ever made. This shift blurs the line between public and private power. When companies control the pipes of global communication, they gain political influence as well. States depend on them for connectivity. But may also fear their dominance. The result is a complex web of partnerships, regulations, and rivalries that shape the global internet. | Prospective | The geopolitics of undersea cables will keep evolving. New routes are planned across the Arctic as melting ice opens shorter paths between Asia and Europe. These projects could shift trade patterns and bring new challenges. The competition between the U.S. and China will likely intensify. It will not just be over who builds the cables. But also, over who sets the rules for how data moves. At the same time, smaller states and regional groups try to ensure that no single power can dominate the world's data arteries. | Decoding geopolitics isn't a job. It's survival. | Joy |

|

Post a Comment

Post a Comment